Notes from the Field: Glynwood’s grass-based systems during the cold and dark months

Rhythms change across the farm throughout the year. In a grazing-based system, the fall and spring bring striking changes for the livestock and their caretakers. The most significant difference is how and where the livestock eat. This shift presents both challenges and welcome relief.

This season we had four ruminant groups on Glynwood’s 70 acres of primary pasture: ewes, weaned lambs, cow-calf pairs, and cattle growing-stock (or “yearlings”). We pay close attention to soil conditions and pasture growth to determine when the animals move from one paddock to the next. During late fall, the ruminants at Glynwood shift from grazing forage that is photosynthesizing and growing to eating stored and stockpiled feed.

The transition time varies from year to year, depending on moisture and temperature patterns throughout the season. The shorter day length decreases the regeneration of forage to a crawl, and a series of hard freezes will stop growth altogether. This year, the significant rain, cooler temperatures through the summer and relatively warm temperatures in the fall provided for a long grazing season here at Glynwood. Our first frost did not come until the first week of November, much later than 2020 when it came mid-September.

Transitioning the animals to their winter diet begins with providing supplemental dry hay or baleage in the pasture. Baleage is fermented hay and is often wrapped in white plastic. You may have seen baleage on the side of fields along the road—they look like giant white marshmallows. In addition to hay and baleage, a third option is stockpiled feed—this is forage left intact on pasture; though no longer growing, it is still nutritious.

Once they are in the barn, the animals are in a bedded pack system. We add bedding (straw and spent hay) daily to provide a dry and clean space. Over many months, we generate a thick pack of bedding mixed with manure. This material becomes a feedstock for our on-site compost creation. We give the cattle and sheep access to outdoor winter paddocks (called sacrifice areas) where they can stroll, ruminate and eat hay.

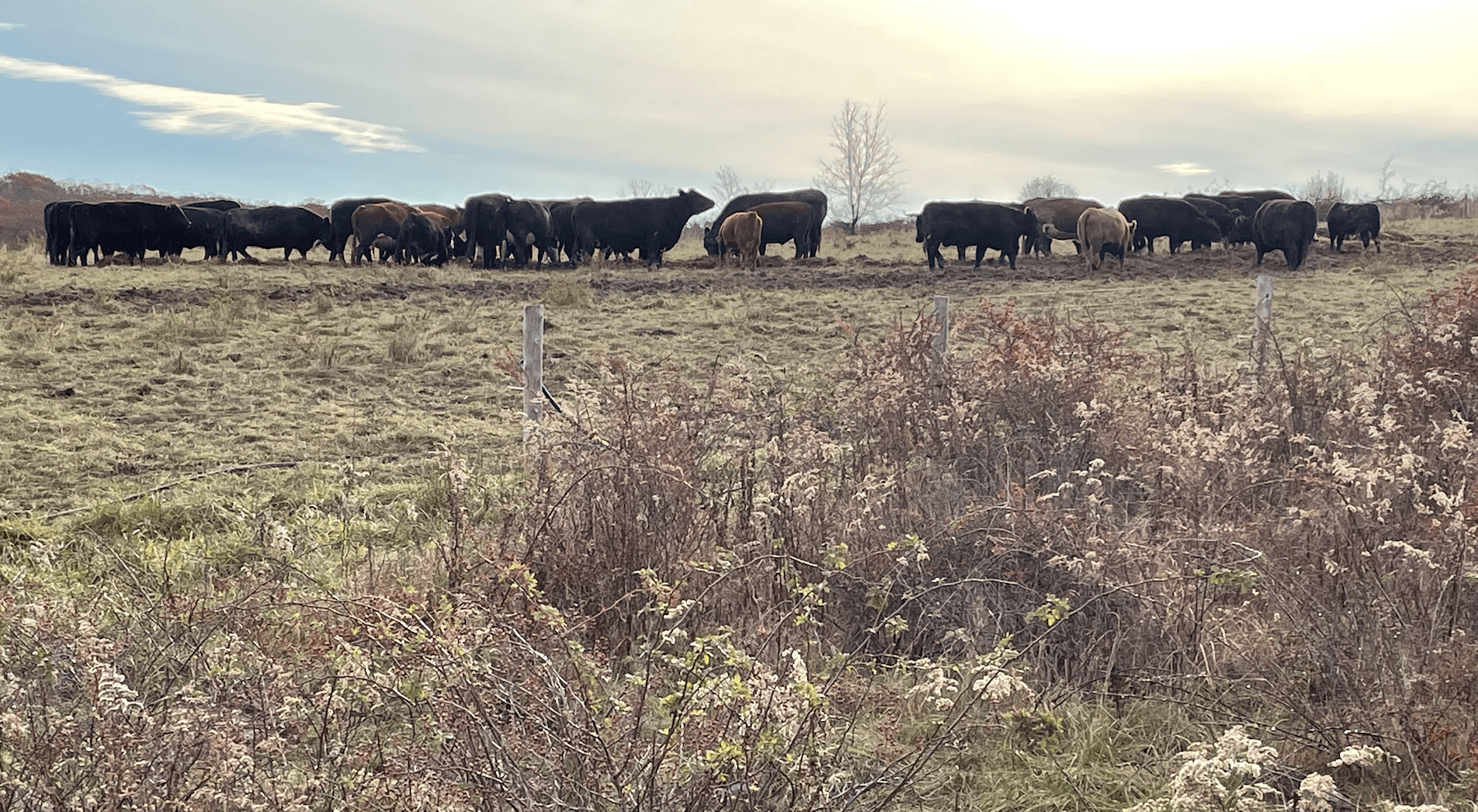

Going forward, especially as our cattle herd grows, we plan to implement more bale grazing on pasture at Glynwood. This means keeping cattle on pasture, away from the barn, and strategically placing hay bales around the field. Bale grazing lets the cows do the work of distributing the manure and forage residue. Ground conditions can make this challenging—wet, cold soil is a combination that could cause hoof issues and/or damage to the pasture and soil. Frozen ground and snow cover is ideal to protect the soil and to keep the cattle dry and clean. The cattle are comfortable without a roof over them as long as they have an adequate windbreak and food to generate body heat. This winter, the cattle feeding strategy will likely involve both feed in the barn and bale grazing on pasture. We will follow the freeze-thaw cycles as we decide when to transition between feeding systems. As winter is coming, it brings relief to have a change of pace, keep the animals close at hand, take stock of the last growing season and look ahead to the next.